#| '!! shinylive warning !!': |

#| shinylive does not work in self-contained HTML documents.

#| Please set `embed-resources: false` in your metadata.

#| standalone: true

#| components: [viewer]

#| viewerHeight: 750

from shiny import App, Inputs, Outputs, Session, render, ui

from shiny import reactive

import numpy as np

from pathlib import Path

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.integrate import odeint

app_ui = ui.page_fluid(

ui.layout_sidebar(

ui.sidebar(

ui.input_slider(id="R_0",label="R_0",min=0.0,max=5.0,value=1.2,step=0.001),

ui.input_slider(id="a",label="a",min=0.0,max=5.0,value=1.2,step=0.001),

ui.input_slider(id="C",label="C",min=0.0,max=5.0,value=1.2,step=0.001),

ui.input_slider(id="N_0",label="N_0 (Initial condition)",min=0.0,max=4.0,value=0.5,step=0.01),

ui.input_slider(id="P_0",label="P_0 (Initial condition)",min=0.0,max=4.0,value=0.5,step=0.01),

ui.input_slider(id="T",label="Number of iterations",min=0.0,max=60.0,value=20.0,step=1.0),

),

ui.output_plot("plot"),

),

)

def server(input, output, session):

@render.plot

def plot():

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

#ax.set_ylim([-2, 2])

# Filter fata

R_0=float(input.R_0())

a=float(input.a())

C=float(input.C())

T=int(input.T())

N_0=float(input.N_0())

P_0=float(input.P_0())

par=[R_0,a,C]

init_cond=[N_0,P_0]

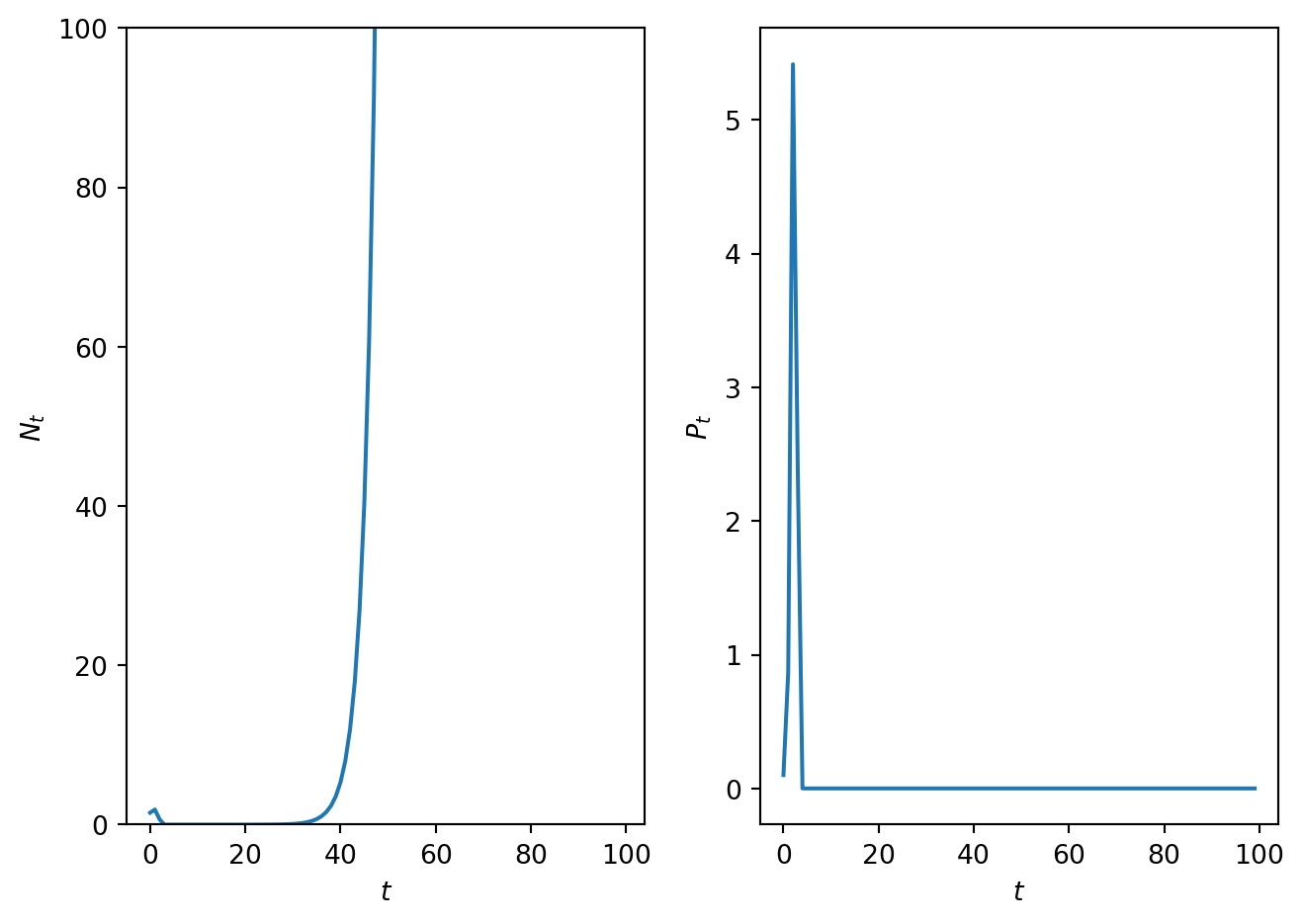

def nicholsonbaileyrhs(x,par):

f=np.zeros_like(x,dtype=float)

N=x[0]

P=x[1]

R_0=par[0]

a=par[1]

C=par[2]

f_nb=np.exp(-a*P)

f[0]=R_0*N*f_nb

f[1]=C*N*(1-f_nb)

return f

# Define rhs of logistic map

# this function computes the solutio to the difference equation. It also stores solution in format for cobweb plotting

def SolveSingleDiffAndCobweb(t,rhs,init_cond,par):

# Initialise solution vector

N = np.zeros_like(t,dtype=float)

P = np.zeros_like(t,dtype=float)

N[0]=init_cond[0]

P[0]=init_cond[1]

# loop over time and compute solution.

for i in t:

if i>0:

sol=[N[i-1],P[i-1]]

rhs_eval=rhs(sol,par)

N[i]=rhs_eval[0]

P[i]=rhs_eval[1]

return N, P

# Define discretised t domain

t = np.arange(0, T, 1)

# define initial conditions

# Compute numerical solution of ODEs

N,P = SolveSingleDiffAndCobweb(t,nicholsonbaileyrhs,init_cond,par)

# Plot results

ax.plot(t,N,t,P)

ax.set_xlabel('$t$')

ax.legend(['$N_t$','$P_t$'])

#ax.set_ylim([0,max_sol])

ax.set_title('Time series')

plt.grid()

plt.show()

app = App(app_ui, server)