Surfaces

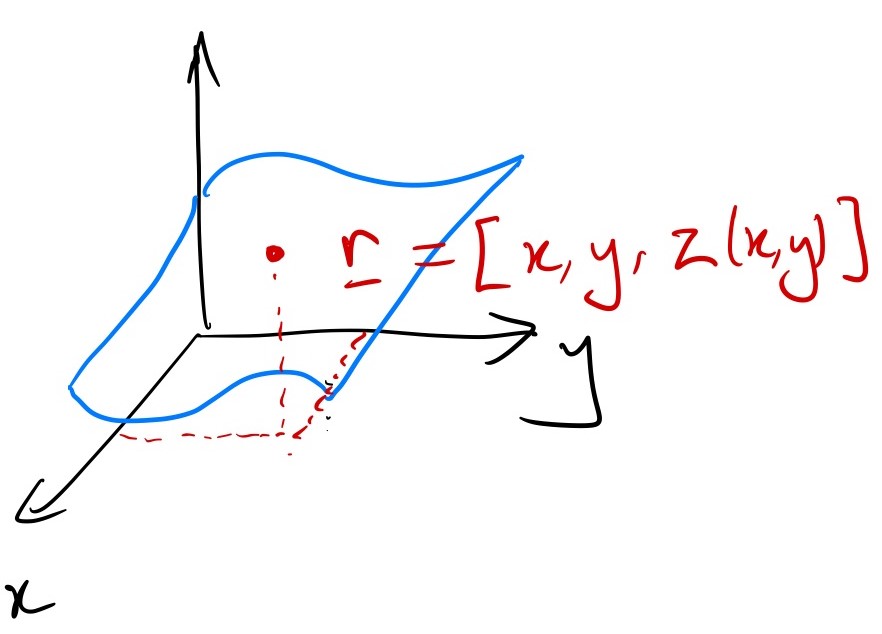

Curves in 3D can be seen as a generalisation of curves in 2D, but a different generalisation would be surfaces in 3D1. The easiest way to write down a surface is \[

z = f(x,y).

\] This is exactly equivalent to \(y=f(x)\) in 2D, and you can think of it as giving the height of the surface at any points \(x\) and \(y\).

Actually, any single equation relating the variables \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) will in general describe a surface in 3D. For example, \[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1 \] is the sphere of radius 1 centred on the origin (MA12001), and \[ x = 1 \] is the plane parallel to the \(y-z\) plane which goes through the point \([1,0,0]\).

If we’re being careful we should write that \[ \{ [x,y,z]\in\mathbb{R}^3 | x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1\} \] is the sphere, rather than just the equation itself. Don’t be afraid if you see this set notation.

Parameterisations of surfaces

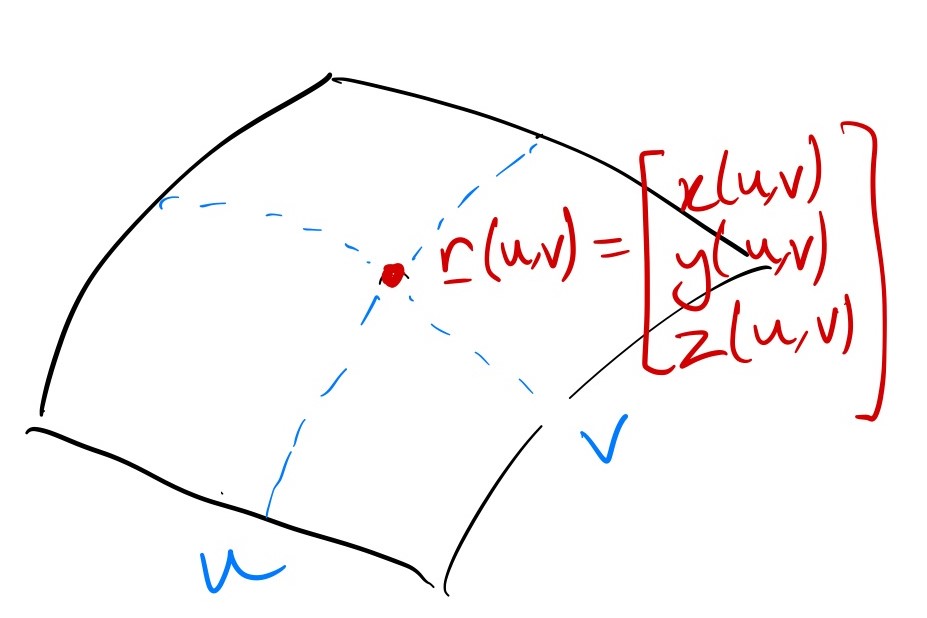

Just as with curves, we can describe surfaces parametrically. However, for a two-dimensional surface, we need two parameters, which we usually call \(u\) and \(v\). \[ {\mathbf{r}} (u,v) = [f(u,v),\,g(u,v),\,h(u,v)] \] and again, we need to specify ranges for the parameters.

Example: parameterisation of a plane

In MA12001, you saw plane equations like \[{\mathbf{r}}\cdot {\mathbf{n}} = d\] where \({\mathbf{n}}\) is a normal vector to the plane (more on this below) and \(d\) is some number. We can transform this to parametric form by introducing \(u=x\) and \(v=y\).

So we need only work out what \(z\) is, as a function of \(u\) and \(v\). Substituting into the equation, \[d = [u,v,z]\cdot[n_1,n_2,n_3] = un_1 + vn_3 + z n_3,\] so \[ z = \frac{d-un_1-vn_2}{n_3} \] so the full parameterisation is \[ {\mathbf{r}}(u,v) = \left[u,\,v,\,\frac{d-un_1-vn_2}{n_3}\right]. \]

Think: When would this parameterisation fail?

If the plane we want to parameterise parallel to the \(y-z\) plane then we cannot use \(u=x\) because \(x\) only has one fixed value.

Then the formulas above result in division by zero, because we would have \(n_3=0\).

Similarly if \(y\) is always the same then we can’t use \(v=y\). But in these cases we can just use \(u=x\), \(v=z\) or \(u=z\), \(v=y\) respectively.

Example: parameterisation of a sphere

The sphere which is described by \[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1 \] can be parameterised as \[ {\mathbf{r}}(u,v) = [\cos u \sin v,\,\sin u \sin v,\cos v], \quad 0\leq u \leq \pi,\quad 0\leq v < 2\pi. \]

Think: How can you show that these points satisfy \(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1\)?

Subsituting in \(x=\cos u \sin v\), \(y=\sin u \sin v\) and \(z=\cos v\), you can see this. You will need to use both \(\cos^2 u + \sin^2 u = 1\) and \(\cos^2 v + \sin^2 v = 1\).

We will talk much more about this when we discuss co-ordinate systems.

Tangents to surfaces

If you fix a value of \(v\), say \(v=v_0\), then for any surface \({\mathbf{r}}(u,v)\), \[{\mathbf{r}} (u) = {\mathbf{r}}(u,v_0)\] just describes a curve in space.

For example, in the sphere parameterisation above, fixing \(v=0\) gives the circle \(x^2+y^2=1\), \(z=0\), which is the equator of the sphere.

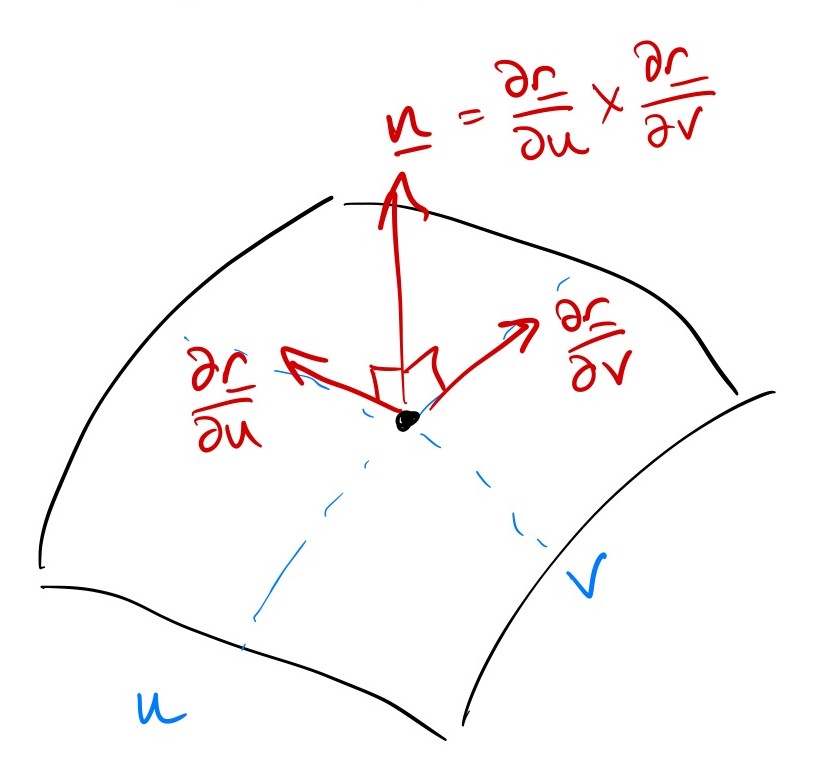

We have already seen that curves have tangent vectors. What is the meaning of these tangent vectors for surfaces? These are just \(\frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial u}\) and \(\frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial v}\), the partial derivatives keeping the other variable constant.

A tangent vector to a surface is any vector which, at the current point, doesn’t point into or out of it. These are \(\frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial u}\) or \(\frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial v}\) or any linear combination, these tangent vectors form a two-dimension space called the tangent space with basis vectors given by \(\frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial u}\) and \(\frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial v}\).

We won’t use surface tangent vectors much except to compute normal vectors.

Normals to surfaces

Surface normals, and the different ways to calculate them, come up a lot later in the module. Make sure you understand this.

Normal vectors \({\mathbf{n}}\) of surfaces are the direct generalisation of normal vectors to planes. They are a vector which makes a right-angle with the surface at a given point. As with tangent vectors for surfaces, normals can point in either direction and the magnitude depends on parameterisation, so sometimes we talk about unit normals.

There are two ways to calculate normal vectors, and which to use depends on the form you have for your surface.

The normal vector is perpendicular to the surface, so in particular it is perpendicular to all tangent vectors at the same point. So we can take the cross product of two different tangent vectors to find the normal.

For a parameterised surface, this means \[ {\mathbf{n}}(u,v) = \frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial v} \]

Alternatively, if you can write your surface as an equation \[ f(x,y,z) = d, \] where \(d\) is some number (often zero), then we can use the formula2 \[ {\mathbf{n}} = \left[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x},\,\frac{\partial f}{\partial y},\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\right]. \]

We’ll see an explanation for why this works in class, but it should become more clear to you after the next unit of the module.

Example: Normal to a sphere

We saw that we can parameterise \[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1 \] as \[ {\mathbf{r}}(u,v) = [\cos u \sin v,\,\sin u \sin v,\cos v], \quad 0\leq u \leq \pi,\quad 0\leq v < 2\pi. \] So we can use both of the methods here. Let’s find a unit normal to the sphere at the point \({\mathbf{r}} = \left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right]\)

Think: is this point on the sphere? What parameters \(u\) and \(v\) does it correspond to?

Subsituting \(x=y=z=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) immediately gives \[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1, \] so it’s on the sphere.

To find \(u\) and \(v\), it’s easiest to start with \(z = \cos v = \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\), so \[v=\cos^{-1} \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}.\]

Then \(\sin v = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{3}}\), and so \(x = \cos u \sin v = \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\) gives \[ \cos u = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \] so finally \[(u,v) = \left(\frac{\pi}{4},\,\cos^{-1} \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right).\]

Cross product

Two different tangent vectors at the point \((u,v)\) are \[ \frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial u} = [-\sin u \sin v,\,\cos u \sin v,\,0] \] and \[ \frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial v} = [\cos u \cos v,\,\sin u \cos v,\,-\sin v], \] so then \[ \begin{aligned} {\mathbf{n}}(u,v) &= \frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial{\mathbf{r}}}{\partial v} \\&= \left[\cos u \sin v\times -\sin v,\,\sin u \sin v\times-\sin v,\,-\sin u \sin v\times\sin u \cos v-\cos u \sin v \times \cos u \cos v\right] \\&= \left[-\cos u \sin^2 v,\,-\sin u \sin^2 v,\,-\sin v \cos v\right] \\&= -\sin v\left[\cos u \sin v, \sin u \sin v, \cos v\right]. \end{aligned} \]

After a lot of manipulation you will find that the magnitude of this is \(\sin v\), so we get a unit normal \[ \hat{{\mathbf{n}}}(u,v) = -\left[\cos u \sin v, \sin u \sin v, \cos v\right], \] which at our point \((u,v) =\left(\frac{\pi}{4},\,\cos^{-1} \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)\) is \[ \hat{{\mathbf{n}}} = -\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right]. \]

Direct differentiation

We have \(f(x,y,z) = x^2 + y^2 + z^2\), so \[ {\mathbf{n}} = \left[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x},\,\frac{\partial f}{\partial y},\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\right] = [2x,2y,2z]. \] and at our point \([x,y,z]=\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right]\) we get \[{\mathbf{n}} = \left[\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\right].\]

For a unit vector, we need to divide by the magnitude of this (which is \(2\)), so the final answer is \[\hat{{\mathbf{n}}} = \left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}},\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right].\]

These two answers are different! They are pointing in opposite directions. One is the inward-facing normal and the other is the outward facing normal. Choosing the right one will become important later on.

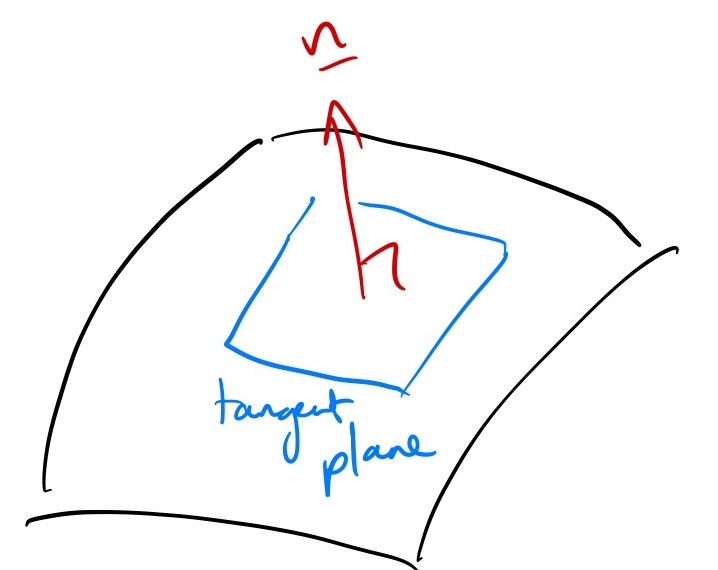

Tangent planes

We said that there are infinitely many different tangent vectors to a surface at a given point. In fact, these tangent vectors all lie on a plane, and we can describe that plane (which is itself a surface) using the formula from MA12001: \[ ({\mathbf{r}}-{\mathbf{c}})\cdot{\mathbf{n}} = 0 \] Here \({\mathbf{r}}\) is any generic point on the plane, \({\mathbf{c}}\) is one specific point and \({\mathbf{n}}\) is the normal to the plane.

So we should take \({\mathbf{c}}\) to be the point on the original surface and \({\mathbf{n}}\) to eb the normal there.

Example: tangent plane to the sphere

Find the tangent plane to the sphere \[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1, \] at the point \([x,y,z] = [1,0,0]\).

The normal is \[{\mathbf{n}} = [2x,2y,2z] = [2,0,0],\] so substituting this and the point into the plane equation we get \[ ([x,y,z] - [1,0,0]])\cdot[2,0,0] = 0 \] which simplifies to \[ 2x-2 = 0 \] or simply \(x=1\). Sketch this: it makes sense.

It’s easy to get confused between generic points on the surface and the tangent plane when you’re doing this sort of problem. Go slowly and make sure your notation is clear.

Surface area

We’ve seen how to calculate the length of curves as an integral, so the obvious extension is to calculate the surface area of surfaces as an integral. We’ll do this in unit 3 of the module.

Footnotes

Curves have dimension 1. But a curve in 2D has co-dimension 1 and a curve in 3D has co-dimension 2, whereas a surface in 3D has co-dimension 1. The co-dimension of a subset is the dimension of the space minus the dimension of the subset. The co-dimension is the number of equations you need to describe a subset.↩︎

In the next unit, we’ll write this as \({\mathbf{n}} = \nabla f\).↩︎