The divergence theorem

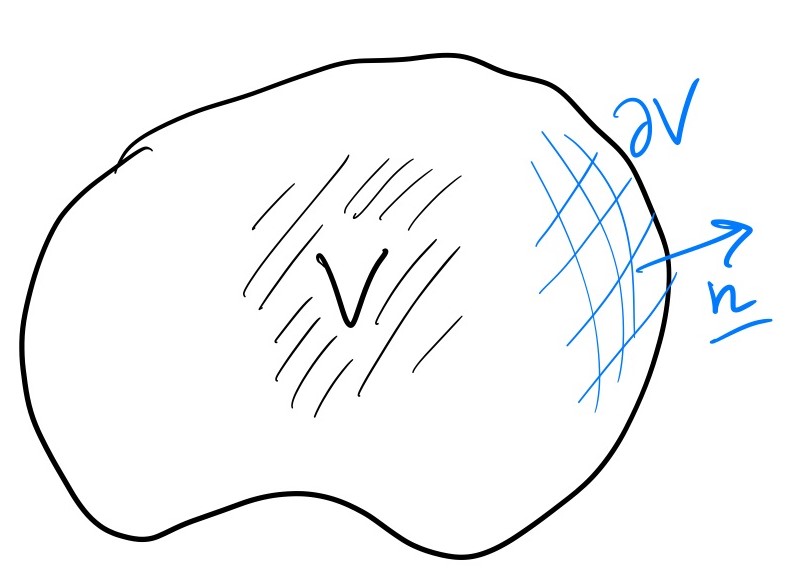

The divergence theorem is similar to Stokes’ theorem, but it relates volumes and surfaces rather than surfaces and curves. As the name suggests, it uses the divergence: \[ \int_V \nabla\cdot {\mathbf{F}}({\mathbf{r}}) dV = \int_{\partial V} {\mathbf{F}}({\mathbf{r}})\cdot d{\mathbf{S}}. \]

The volume integral of the divergence of a vector field over a volume \(V\) is the flux integral of the vector field over \(\partial V\).

As you may be able to guess, \(\partial V\) is the boundary of the volume \(V\), with the normal facing out. Again, we may need to do the boundary in more than one piece.

Example

Let \(V\) be the solid cylinder \(x^2+y^2\leq 1\), \(0\leq z \leq 2\). Calculate, both directly and using the divergence theorem, the volume integral \[ \int_V 2z\, dV \]

Directly

Since \(V\) is the cylinder \(x^2 + y^2 \leq 1\), \(0 \leq z \leq 2\), we can use cylindrical coordinates: \[ x = \rho\cos\phi,\quad y = \rho\sin\phi,\quad z = z,\quad 0 \leq \rho \leq 1,\ 0 \leq \phi < 2\pi,\ 0 \leq z \leq 2 \]

The volume element is \(dV = \rho\,d\rho\,d\phi\,dz\).

So, \[ \begin{aligned} \int_V 2z\,dV &= \int_{0}^2 dz\int_{0}^1 d\rho \int_{0}^{2\pi} d\phi 2z\rho\\ &= \left(\int_{0}^2 2z dz\right)\left( \int_{0}^1 \rho\,d\rho \right) \left( \int_{0}^{2\pi} d\phi \right) \\&= 4\pi. \end{aligned} \]

Divergence theorem

To apply the divergence theorem, we need to find some \({\mathbf{F}}\) such that \(\nabla\cdot{\mathbf{F}}=2z\).

\[{\mathbf{F}} = [0,0,z^2]\] works (more on this next week). So we need to calculate \[ \int_{\partial V} [0,0,z^2]\cdot d{\mathbf{S}} \]

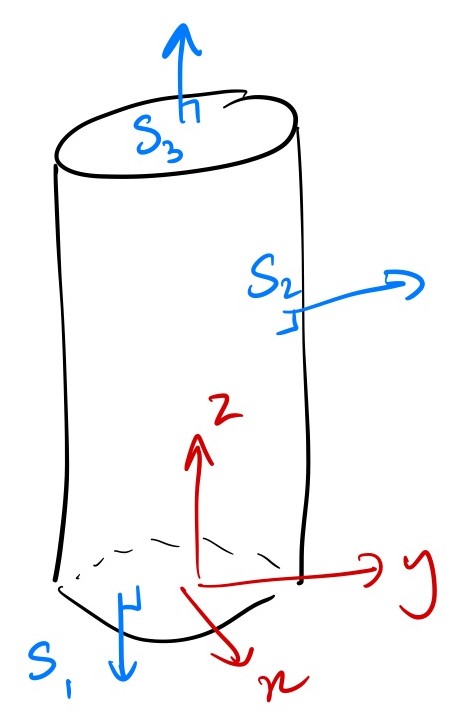

In this case, \(\partial V\) has three parts that we’ll call \(S_1\), \(S_2\) and \(S_3\).

On the base \(S_1\), the field \({\mathbf{F}}\) is zero because \(z=0\), so \[\int_{S_1} [0,0,z^2]\cdot d{\mathbf{S}} = 0\]

On the curved surface \(S_2\), the normal \(\hat{\mathbf{n}}\) is horizontal, and the field \({\mathbf{F}}\) is only in the \(z\) direction, so \({\mathbf{F}}\cdot d{\mathbf{S}}=0\), so \[\int_{S_2} [0,0,z^2]\cdot d{\mathbf{S}} = 0\]

On the top \(S_3\), \({\mathbf{F}} = [0,0,4]\) which is parallel to the outward-pointing normal \(\hat{{\mathbf{n}}}\), so the surface integral gives \[\int_{S_3} {\mathbf{F}}\cdot d{\mathbf{S}} = \int_{S_3} [0,0,4]\cdot \hat{{\mathbf{n}}}\, dS = 4 \int_{S_3} dS = 4\pi\] because \(\int_{S_3} dS\) is just the area of the circle.

So the divergence theorem gives us \(\int_V 2z\,dV = 4\pi\), as before.

Green’s identities

These two results are easy to prove once you know the divergence theorem, and they turn out to be helpful in many situations in physics. They also give good insight into how the divergence theorem can be used.

Green’s first identity

Green’s first identity states that, for any scalar fields \(f\) and \(g\), \[ \int_V \left(g\Delta f + \nabla f \cdot \nabla g\right)dV = \int_{\partial V} g\nabla f \cdot d{\mathbf{S}}. \]

To prove this, we obviously need to use the divergence theorem. It’s not clear how we can use that on the left-hand side, so let’s start with the right-hand side and use the product rule: \[ \begin{aligned} \int_{\partial V} g\nabla f \cdot d{\mathbf{S}} &= \int_{V} \nabla \cdot \left(g\nabla f\right) dV \\ &= \int_{V} \left(\nabla g \cdot \nabla f + g\nabla\cdot\nabla f \right) dV \end{aligned} \] which is exactly what we wanted, when we remember that \(\Delta f = \nabla\cdot\nabla f\).

Green’s second identity

Green’s second identity states that, for any scalar fields \(f\) and \(g\), \[ \int_V \left(f\Delta g - g\Delta f\right)dV = \int_{\partial V} \left(f\nabla g - g\nabla f\right) \cdot d{\mathbf{S}}. \] You can get this one from subtracting the first identity from itself with \(f\) and \(g\) swapped.

This one is quite handy when you rearrange it: \[ \int_V f\Delta g\ dV = \int_{\partial V} \left(f\nabla g - g\nabla f\right) \cdot d{\mathbf{S}} + \int_V g\Delta f\ dV. \] This is basically a form of integration by parts for the Laplacian \(\Delta\).